Ten Charitable Planning Mistakes to Avoid

by Vaughn Henry and Johni Hays

This article highlights specific areas of the charitable planning process where mistakes seem to re-occur based on the authors combined experiences as charitable planning consultants. Newcomers to the field of planned giving arent the only ones making mistakes because as you read through the article, youll see that all types of planners, from the seasoned professional to the charitable planning novice, show up in the following examples. By sharing real-life situations, the authors hope to provide practical experience and knowledge from the trenches, not from the painful school of hard knocks, but via the less painful old cliché, learn from the mistakes of others.

1. Not Putting the Donors Interests Ahead of All Others

As planners work together as a team to recommend a charitable plan for clients, it is imperative to always put the clients interests ahead of the charity, the attorney, the CPA, and the agent. It seems like a statement of the obvious, but sometimes a plan can seem so good, the planner doesnt want to throw water on the proposal by bringing up the possible downsides. Heres a case where the planners went a step further down the wrong path by intentionally omitting relevant information the donors needed.

In the case of Martin v. Ohio State University Foundation (Ohio App., 10th App. Distr., 2000), the donors of a NIMCRUT sued their life insurance agent, the life insurance company, and the charity that also acted as their NIMCRUTs trustee. An attorney and an insurance agent proposed a charitable plan to a couple that included the donation of $1.3 million of undeveloped farmland to a NIMCRUT. The donors would use income from the NIMCRUT to purchase a $1,000,000 life insurance policy costing $40,000 per year for wealth replacement for the donors children.

The donors received several proposals over the course of a few months. Each and every proposal showed the NIMCRUT paying the donors income immediately after the execution of the NIMCRUT. Since the donors annual income prior to the transaction was only $24,000, the donor was counting on the trust income to pay the insurance premiums.

The charitys representative wrote a comment on the last proposal shown to the donors that a net income trust funded with non-income producing land cant make any income payments until after the land is sold. When the insurance agent saw the comment on the proposal, he deleted it before giving it to the donors. Unfortunately, the land was not sold until two and one-half years later and no income was paid to the donors during that time. In the meantime the agent tried to loan the clients enough money to pay the insurance premiums, but in the end the policy lapsed. The donors sued for fraud, negligent misrepresentation, breach of contract and breach of fiduciary duty asserting they had never been told the truth about income not being payable from the NIMCRUT until after the land was sold.

In the Martin case, the advisors failed to give the donors accurate and complete information as to how the charitable gift would work in their situation. They intentionally deceived the clients for what appears to be their own financial gain. At all times and in all aspects of planning with clients, the goal must be to provide advice that is in the clients best interests, not the planners. Clients deserve the best and accurate advice from their planners even if it prevents the gift from occurring.

2. Recommending a Charitable Gift Without a Full Understanding of the Donors Financial Needs and Goals

A few planners tend to sell a charitable gift like a financial product. A charitable gift is not a product; its part of an integrated estate and charitable planning process. To illustrate, one planner wanted to set up a CRAT for an older client funded with farm-land. The planner had a fixed annuity he wanted to sell to the trustee using the proceeds from the land. The planner was under the impression the trust was required to purchase an annuity since it was a charitable remainder annuity trust. The planner was then counseled on how a well-balanced mutual fund might be a more suitable vehicle for the proceeds. Unfortunately, the planner responded he wasnt licensed to sell mutual funds.

Upon further learning that the annuity would produce tier one ordinary income at the clients marginal income tax bracket of 42%, the planner replied that since his client would be obtaining a large income tax deduction he could afford to pay more in income taxes.

Sadly, this situation represents a product-selling planner who isnt mindful of the downside of recommending the CRT. The planner did not ascertain his clients charitable interests, instead he recommended the concept as a means to avoid or even evade capital gains taxes when in fact, it would potentially increase his clients tax liabilities. The recommendations made for this plan werent in the clients best interests and could be considered malpractice on the part of the planner.

3. Serving As Trustee

Another misstep can occur during the charitable planning process when the advisor serves as the trustee for either the clients life insurance or charitable trust. Financial planners, brokers and insurance agents need to be careful when asked by their clients to serve as the trustee. The best answer to give a client is No, thank you. Serving as trustee can create a serious conflict of interest if the trustee benefits by the transaction, not to mention SEC problems if the agent or broker has a securities license.

If the life insurance agent is selling the policy to the trustee when he also serves as trustee, he is selling a product to himself for which he earns a commission using someones elses money. Its a conflict of interest and it is best to leave the trustee’s duties to a trust professional.

Generally, non-legal advisors are not well trained in the duties imposed on the trustee as a fiduciary. Moreover, non-legal advisors are generally not trained to understand the language used in trust documents and what each paragraph means in laymans terms. Moreover, most insurance companies will not allow their agents to act as trustees for trusts funded with their own insurance policies. Additionally, most E&O coverage does not cover acts by an insurance agent acting as a trustee.

For many reasons even attorneys are reluctant to serve as trustees because attorneys know all too well the complex duties involved when acting as a fiduciary and following the prudent investor rules. One trust officer, who found out too late what the trustees duties are, served as the trustee of a testamentary CRAT. He asked how long he could wait to begin making payments to the income beneficiaries as the land inside the CRAT hadnt sold and there were no other assets inside the trust. Three years later, the income beneficiaries still hadnt received their first income payment from a trust that has no legal recourse but to distribute income or assets annually, whether its liquid or not.

4. Donating Inappropriate Assets

A charitable planner can find himself in an uncomfortable position when he is unfamiliar with the consequences making gifts using various assets. The tax rules covering charitable deductions for different kinds of assets can be complex, so the best way to prevent these types of mistakes from happening is to know the rules for each type of asset.

To illustrate, one planner suggested a client donate $3,000,000 of art to a CRUT using a 10% income payment. Even though the client properly executed the CRUT, the client continued to display the artwork in his home. The planner mistakenly thought the charity would advance the 10% income payment to the trust each year, and he did not know the artwork couldnt be kept indefinitely on display at the clients home. To make matters worse, the charitable deduction was not based on the artworks fair market value like the planner told the donor, but instead the deduction for tangible personal property that has no “related use” to the trust was based on the donors lower cost basis.

Another planner was working with a client whose only other asset beyond $75,000 of mutual funds was a $350,000 IRA. The planner didnt realize the entire IRA would be subject to income taxes if the client donated it to charity in exchange for a charitable gift annuity. Adding to the misunderstanding was the offending charitys IRA Donation proposal which failed to adequately disclose the disadvantages of using an IRA for a charitable gift under current tax laws. (Note: proposed legislation, if enacted into law, may allow IRAs to be given to charities during the donors lifetime without incurring a taxable event. See Senate Bill S-1924.)

A financial planner, who also wasnt aware of the consequences of donating the specific asset he recommended, knew his client was coming into a large sum of money soon from the sale of his business. The planner recommended that his client quickly donate the business to a CRT to help his client avoid taxes. Upon discovery, however, the client had actually sold his entire business five years ago and this large sum of money was the final payment in a series of installment payments for the buyout.

Donating Various Types of Assets

These assets need extra special handling:

· Encumbered real estate

· Closely held “C” corporation stock

· Restricted (Rule 144) stock

· Stock with a tender offer in place

· Sole proprietorships, partnerships and on-going businesses

· “S” corporation stock

These assets should generally be avoided in charitable gift planning:

· Property with an existing sales agreement

· Installment notes

· Stock options (both qualified Incentive Stock Options and nonqualified stock options)

· Lifetime transfers of IRAs and Qualified plan dollars

· Lifetime transfers of commercial deferred annuities

· Lifetime transfers of savings bonds

5. Reinvesting CRT Assets Improperly

Often times a charitable trust is put together by a financial advisor or insurance agent with the hopes that the donor, who generally serves as trustee, will look to the advisor or agent to reinvest the proceeds of the gifted asset once its sold. While there is nothing wrong with this plan, advisors need to be educated on the complexities associated with prudent investor rules, charitable trust accounting, tax deductions, etc., before they can fully understand the consequences of their recommendations.

An example of improperly invested CRT assets occurred when a planner recommended his middle-aged donor establish a CRAT. Inside the CRAT the donor-trustee bought a life-only single premium immediate annuity to guarantee the annuity income payable to the income beneficiary. The flaw underlining this transaction is that the charitys remainder interest would be left without any assets when the trust terminates, as a single premium immediate annuity for life only will end upon the death of the client with no principal balance leftover. This recommendation could make the trust subject to oversight by the state’s Attorney General for imprudent investment and all its advisors are potentially liable to the charity Remember, a CRT is a split interest gift, and there are two beneficiary groups with a legal interest in these tools, so the trustee often must wear two hats, one as an income beneficiary and one looking out for the charity’s well being.

To compound an already unpleasant situation, when the planner was counseled regarding the flaw in his proposal, he and the lawyer argued that the trustees purchase was valid because the trust passed the 10% test. The planner and lawyer were then counseled on the difference between the 10% test in terms of the charitable deduction and subsequently investing CRT assets improperly.

Another planner, who also recommended a similar plan, suggested his trustee purchase a life insurance policy to pay the charity its portion when the immediate annuity payments end. However, this plan was similarly destined for failure as the CRAT cannot accept ongoing contributions to pay a lifetime of insurance premiums

Improper investing occurred with a stockbroker who chose to invest his clients CRT funds with several partnerships (creating UBTI) in the first year of the CRT’s existence. This choice created a taxable CRT that does not avoid the capital gains liability when the appreciated asset that funded the CRT was sold. In addition, there was no income tax deduction to offset the reinvestment error, compounding the broker’s poor advice. Other mishaps have occurred when the trustees were given access to a charge card on a money market account held inside a CRT. Trustees with charge cards on CRT assets open up self-dealing and debt financed problems similar to trading on margin accounts and charging the CRT interest on the loan when the trades do not materialize as expected.

If a planner “sells a CRT”as a way to take assets under management or sell wealth replacement, it isnt unethical but it sure can be short sighted. Its also likely to result in unhappy clients who find themselves stuck with an irrevocable plan that doesnt meet their needs. Agents and planners who recommend charitable gifts must be knowledgeable of charitable gift laws and be prepared to pull in a team of experts to implement a plan in the donors best interests.

Learn from the mistake of an insurance company that allowed a commercial deferred annuity to be removed from inside a CRT. The CRTs trustee was the owner and beneficiary of the annuity and the husband was the annuitant. At the husbands death, the death claim papers were sent to the surviving spouse who checked the box on the claim form allowing the surviving spouse to change the ownership of the annuity to her own name as an individual. She then withdrew all the interest earnings in the annuity. The error wasnt caught until the spouse complained of the large IRS Form 1099 she received the following January for the interest income she received. This is often a problem in a NIMCRUT using a deferred annuity when the insurance company incorrectly sends out a 1099 to the annuitant, instead of to the tax-exempt CRT, while the CRT is properly issuing a K-1 for the same income distributions, thus doubling the income tax exposure.

Understanding the four-tiered system of accounting in a CRT can seem complex. Often planners may not fully comprehend all the issues involved and this leads to mistakes. For instance, one attorney counseled his client to fund a CRT with farmland. He had the trustee purchase tax free municipal bonds after the land sold to obtain tax-free income from the CRT. However, what the professional didnt realize, is how the capital gain income from the sale of the real estate is higher on the 4 tier accounting system than any new tax free income generated by the municipal bonds. Understandably, the client was quite unhappy when the income wasnt tax-free.

6. Not Monitoring the Wealth Replacement Sale

A charitable planning case can be effectively implemented with the appropriate professionals including the clients attorney, CPA, planned giving officer, and the life insurance agent. However, in charitable plans where life insurance is a part of the overall plan, the purchase of life insurance inside an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT) should be monitored by the donors estate planning attorney. Attorneys should direct the process and clearly indicate to the donor, the trustee, and the life insurance agent how the process should work and in what order each step should occur. Otherwise, what can happen is the insurance sale can be implemented in a way that undermines the donors estate plan. The following are life insurance missteps that can cost clients hundreds of thousands of dollars in estate or gifts taxes.

1) The insurance policy is issued prior to the life insurance trusts implementation. This occurs when the insurance agent issues the policy before the irrevocable trust is executed and funded. If the policy is applied for before the trust is executed, it is commonly applied with the insured as the policy owner. If the ownership is thereafter transferred to the irrevocable trust, the threeyear in contemplation of death rule occurs causing the policy to be pulled back into insureds estate if he dies within three years of the transfer.

Its a preferred practice to have the donors insurability determined using trial applications, but once insurability is approved, the policy should not be issued until the ILIT is executed, funded, and withdrawal power letter have been sent to trust beneficiaries and the Crummey powers lapse. At that point the agent submits completely new applications with the trustee as the owner and beneficiary. The trustee then pays the premium to the agent and the policy is then officially issued.

2) The insurance agent accepts the premiums directly from the insured and applies those premiums to the policy owned by the ILIT The proper procedure requires that the agent obtain the premium check from the trustees funds, not from the insureds personal funds, when the trust beneficiaries have withdrawal powers. The goal is to have the trust funded and the withdrawal beneficiaries notified and their right to those annual exclusion gifts lapse prior to the trustee paying the premium.

If, on the other hand, the agent obtains a premium check directly from the donors personal funds, the premium amount is not considered a gift of present interest since the trustee never had the funds, nor have the beneficiaries been notified of their withdrawal rights and therefore, their gifts cannot fall within the annual exclusion gift amount. The insured must file a gift tax return for these gifts and use part of his estate tax exemption equivalent of the unified credit (currently $1,000,000) to cover the premiums.

7. Selling the Numbers on a Charitable Illustration.

The various illustrations from charitable planning software vendors are generally provided to prospective donors to give them diagrams or flowcharts to describe the type of charitable gift being presented. The mistakes made when presenting these illustrations arise from a misunderstanding of the variables behind the illustration. For example, a common mistake is to create a CRT with a non-spouse as an income beneficiary, e.g., mom, dad and child, and the illustrations are cranked out without any cautionary words about the loss of the unlimited marital deduction and the effect of taxable gifts with a CRT being included in the trustmaker’s estate. The software produces the correct “income tax deduction,” but does not address the more complex gift or estate tax issues.

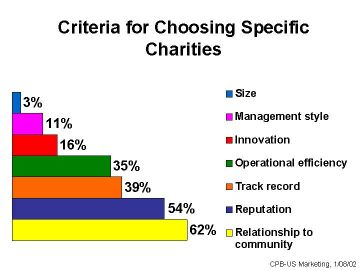

The charitable planner must know the variables that produced these calculations and numbers. The planner must know and understand the footnotes and assumption behind every proposal. With a charitable remainder trust, for example, the planner needs to know what interest rate is being used to assume the future growth of the CRT assets. In addition, the interest rate must be a reasonable number. In turn, the planner must inform the client of the variables used in the illustration. The client must know what numbers he can rely on and those he cannot. Its simply an education process, and the more the client knows and understands, the better and happier the client will be.

8. Selling Charitable Gift Annuities

Planners new to the field of charitable giving frequently have a misconception surrounding a charitable gift annuity. Since planners may sell commercial annuities to clients for commissions, they sometimes assume that a charitable gift annuity is an annuity offered for sale to the public from their insurance company.

However, a charitable gift annuity is not a commercial annuity offered by a life insurance company. It can only be offered by a charity and is an agreement between a donor and a charity in which the donor gifts an asset to a charity in exchange for lifetime income for the donor. The income provided to the donor from the charitable gift annuity is always paid by the charity.

The young planner who was asked to work with a particular charity’s donors to conduct seminars and help establish charitable gift annuities best illustrates this misconception. The planner thought the insurance company had an annuity for him to sell at the seminar and that he would be earning a commission on each charitable gift annuity sold. The agent asked if these donors would be bringing their checkbooks to the seminar and if these gift annuities are mostly one-interview sales.

To make the confusion even worse, a few charities are under IRS scrutiny for their practice of paying advisors a finders fee for bringing clients to establish a charitable gift annuity with them. Not only are these practices considered highly unethical by some professional advisors, but also it may be a violation of the Philanthropy Protection Act of 1995. An advisor cannot help fulfill the donors charitable mission and values by giving donations to causes in which the client feels strongly if the advisor steers all potential donors to only one charity the one that will pay him a finders fee.

9. Unknowingly Practicing Law Without A License

The unauthorized practice law is generally thought to be committed by a non-lawyer when that person provides legal advice to another either verbally or through the drafting of legal documents. The unauthorized practice of law can occur in charitable and estate planning through the misuse of computerized legal documents also known as specimen documents.

The reason for providing specimen documents is so the planner can bring something to the planning process as a value added service for the clients attorney. These sample documents are intended for use by the clients attorney when that attorney may not be an expert in the field and could use a starting point in drafting. Its a way for the agent to be professional and helpful in the planning process.

Unfortunately, the planner or the client can misuse these specimen documents. Some non-lawyers have asked if they can just fill in these blanks because their client doesnt want to pay an attorney. Whether it is a specimen life insurance trust or a charitable remainder trust, many costly errors have been made when a non-lawyer or donor takes the position that one document fits all and fills in the blanks of a specimen document. Further, many of these specimen trust agreements are ineffective as they are based on IRS prototype documents that are too rigid and don’t provide donors with the flexibility to create a legitimate planning tool that meets their unique needs.

Form books can also get a professional in trouble. One attorney who hurriedly drafted a trust for his client found this out the hard way after inserting boilerplate language from a forms book. The language gave the trustee of the CRT the power to pledge trust assets and to borrow funds;those powers put the exempt status of the CRT at risk.

Charitable gifts are complex and the laws with respect to charitable giving as well as property law can and will vary by the donors particular state law. Specimen documents do not take into account any state law nuances. In fact, for this very reason, the practice of providing specimen documents to planners has caused enough litigation to stop some insurance companies from supplying these documents

10. Recommending Aggressive Charitable Techniques

Planners could scuff their professional reputations when they are involved in aggressive planning techniques and later the IRS or the courts condemn the plan they once recommended. One of the most recently promoted aggressive charitable planning arrangements was charitable split or reverse split dollar. This was an idea whereby the donor purchased a policy and had the death benefit split between the charity and the donors family. However, the donor took a charitable deduction for the entire premium knowing that the donors family would personally benefit from this transaction. Sure enough, in 1999 charitable reverse split dollar arrangements were shot down by Congress [H.R. 1180, the Tax Relief Extension Act of 1999] and the IRS handed down some severe penalties in IRS Notice 99-36, 1999-26 I.R.B. 1.

Some life insurance companies refused to accept or underwrite business from their agents if this concept was behind the life insurance sale. Other companies accepted the life insurance premiums without passing judgment on how that business came to the insurance company or how the agent advised their clients on tax deductibility.

Even though Congress has passed legislation stopping this charitable tax technique, its promoters are still using this concept. The latest version of the technique uses a charitable remainder trust that owns life insurance under the disguise that the donor-income beneficiary is an employee of the charitable remainder trust. The trust is employing the donor-income beneficiary and hence the charitable plan now falls within the employment context of split dollar funded life insurance and thus, outside of the prohibiting legislation However, this plan may raise self-dealing issues that will be sure to capture the attention of the IRS.

Conclusion

The above article demonstrates the pitfalls that planners want to stay clear of as they work to help clients in the area of charitable planning. Take this as a great opportunity to learn from the mistakes made by others and avoid the pitfalls in your practice.

Clients need complete disclosure of the advantages and disadvantages of the plan being proposed. Wellinformed clients tend to be appreciative of the extra effort and it is an important factor in client satisfaction surveys. Take the extra time and make sure the clients charitable plan is proposed with the clients best interests first.

Vaughn Henrys consultancy, Henry & Associates, specializes in gift and estate planning services, wealth conservation and multi-generational family entities. Vaughn also owns http://www.gift-estate.com/, a frequently updated wealth planning resource Web site, and resides in Springfield, IL.

Johni Hays is the Director of Advanced Markets for AmerUs Life Insurance Company in Des Moines, Iowa. She is also the co-author of the book The Tools and Techniques of Charitable Giving, published by The National Underwriter Company. She can be reached at [email protected]

Vaughn W. Henry

Vaughn Henry provides training and consulting services on the charitable estate planning process. As an independent advisor to charitable organizations on planned giving, Vaughn’s clients include some of the Forbes 400 and large U.S. corporations. His consultancy, Henry & Associates, specializes in gift and estate planning services, wealth conservation, and domestic and international financial services.

Since 1977, Vaughn has been a widely recognized and popular presenter to charitable groups, business owners, accountants, attorneys and financial services providers. He specializes in deferred gifting and the Economic Citizenship concept, and creative gifting for the Reluctant Donor. He helps charities learn how to develop larger gifts from difficult prospects and to work more cooperatively with donor advisors.

Vaughn received his BS in Agricultural Science and MS in Animal Science from the University of Illinois and is completing work toward a Ph.D. in management. Prior to consulting, he taught at the college level where he generated entrepreneurial funding for college programs. He continues to consult farm, ranch and closely held family businesses in operational and management techniques, specializing in small business communication technology, human resources training, operations, management and multi-generational estate planning. He is a licensed insurance and securities practitioner. Vaughn owns www.gift-estate.com, a frequently updated wealth planning resource Web site, and resides in Springfield, IL.

In addition to serving on the board of the National Association of Philanthropic Planners, Vaughn’s affiliations include the Sangamon Valley Estate Planning Council, Central Illinois Planned Giving Council (NCPG) and numerous trade and professional financial services organizations. He has been featured in many professional publications, including The Wall Street Journal, Worth, Forbes, Investors Business Daily, Journal of Practical Estate Planning, Planned Giving Design Center, Leimberg Services Newsletters, Planned Gifts Counselor, and Planned Giving Today.

Johni Hays, JD, CLU

Johni Hays is Director of Advanced Markets for a Midwest life insurance company.

Johni has extensive experience in estate and business planning, life insurance planning, charitable giving, retirement planning, annuities, and federal taxation. She has lectured extensively on estate, business and retirement planning in addition to publishing articles nationally on charitable giving. Johni is a co-author of the book The Tools and Techniques of Charitable Giving, published by The National Underwriter Company and is the charitable giving commentator for Steve Leimbergs electronic newsletter service, Leimberg Information Services, Inc., (LISI).

Johni was previously Advanced Markets Counsel for ManuLife Financial in their U.S. headquarters in Boston. In addition, Johni served as an estate planning attorney with Myers Krause & Stevens, Chartered law firm in Naples, Florida, where she specialized in life insurance as a part of the overall estate plan. She also was with Principal Mutual Life Insurance Company for nine years as a marketing consultant in the Mature Market Center in Des Moines.

Johni graduated cum laude with a Juris Doctor degree from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa in 1993. She also holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration from Drake University where she majored in insurance, and graduated magna cum laude in 1988.

Johni is a member of the National Council on Planned Giving, the Mid-Iowa Planned Giving Council, the Mid-Iowa Estate & Financial Planners Council, and the State Education Council for Leave a Legacy – Iowa. Johni is a Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU) and a Fellow of the Life Management Institute (FLMI), and she has been a member of both the Iowa Bar and the Florida Bar since 1993. She can be reached at [email protected]

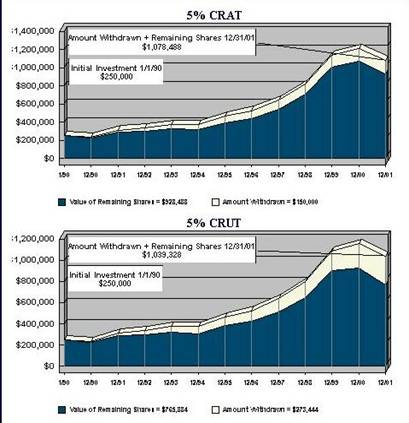

![]()

CONTACT US FOR A FREE PRELIMINARY CASE STUDY FOR YOUR OWN CRT SCENARIO or try your own at Donor Direct. Please note — there’s much more to estate and charitable planning than simply running software calculations, but it does give you a chance to see how the calculations affect some of the design considerations. This is not “do it yourself brain surgery”. When is a CRUT superior to a CRAT? Which type of CRT is best used with which assets? Although it may be counter-intuitive, sometimes a lower payout CRUT makes more sense and pays more total income to beneficiaries. Why? When to use a CLUT vs. CLAT and the traps in each lead trust. Which tools work best in which planning scenarios? Check with our office for solutions to this alphabet soup of planned giving tools.

CONTACT US FOR A FREE PRELIMINARY CASE STUDY FOR YOUR OWN CRT SCENARIO or try your own at Donor Direct. Please note — there’s much more to estate and charitable planning than simply running software calculations, but it does give you a chance to see how the calculations affect some of the design considerations. This is not “do it yourself brain surgery”. When is a CRUT superior to a CRAT? Which type of CRT is best used with which assets? Although it may be counter-intuitive, sometimes a lower payout CRUT makes more sense and pays more total income to beneficiaries. Why? When to use a CLUT vs. CLAT and the traps in each lead trust. Which tools work best in which planning scenarios? Check with our office for solutions to this alphabet soup of planned giving tools.

“Give my stuff to charity! What kind of crazy estate plan is that?” is a typical client response. When they ask about ways to eliminate unnecessary estate taxes and are told to make gifts during lifetime that’s an understandable reaction. It’s not intuitively obvious how giving away something the client may need can be a good thing, especially if the potential donor was raised during the Depression. The epiphany comes when the client looks at the choices they have for assets not consumed to support their lifestyle; those remaining assets can only go to children, charity or Congress. Once the options are explored, many people make a decision to pass some property to heirs and other things to charities that either had or will have some impact on their family’s life. How can they be smarter making that decision?

“Give my stuff to charity! What kind of crazy estate plan is that?” is a typical client response. When they ask about ways to eliminate unnecessary estate taxes and are told to make gifts during lifetime that’s an understandable reaction. It’s not intuitively obvious how giving away something the client may need can be a good thing, especially if the potential donor was raised during the Depression. The epiphany comes when the client looks at the choices they have for assets not consumed to support their lifestyle; those remaining assets can only go to children, charity or Congress. Once the options are explored, many people make a decision to pass some property to heirs and other things to charities that either had or will have some impact on their family’s life. How can they be smarter making that decision?

Vaughn W. Henry

Vaughn W. Henry

Vaughn W. Henry

Vaughn W. Henry CONTACT US FOR A FREE PRELIMINARY CASE STUDY FOR YOUR OWN CRT SCENARIO or try your own at

CONTACT US FOR A FREE PRELIMINARY CASE STUDY FOR YOUR OWN CRT SCENARIO or try your own at

“This site contains links to other Internet sites. These links are not endorsements of any products or services in such sites, and no information in such site has been endorsed or approved by this site.”

“This site contains links to other Internet sites. These links are not endorsements of any products or services in such sites, and no information in such site has been endorsed or approved by this site.”